概要

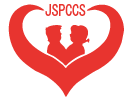

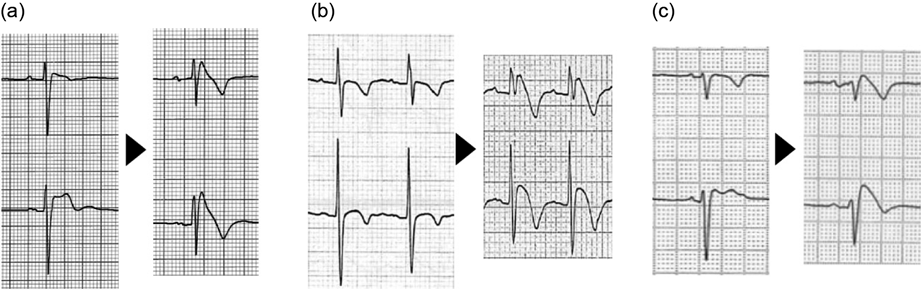

Brugada症候群(BrS)は,12誘導心電図における右脚ブロックパターンと右側胸部誘導のST上昇を特徴とするBrugada型心電図を特徴とし,心室細動(VF)による突然死を引き起こす致死性遺伝性不整脈疾患である.1992年,Brugada兄弟が小児を含む8例について初めて報告した1).右側胸部誘導におけるST上昇は,coved型(type1)とsaddleback型(type2)という特徴的な形態を示す(Fig. 1).東南アジア,東アジアを中心に,中年男性が入眠中に突然亡くなる事象は古くから知られており,ポックリ病(日本),Lai-tai(タイ),Bangungut(フィリピン)などと呼ばれていたが,現在ではこれらの一部はBrSが原因であると考えられている2).近年,その遺伝的背景と電気生理学的機序が明らかとなりつつあるが,発症機序や遺伝的因子を含むリスク層別化などの点において,まだ多くの議論が残っている.

病態生理

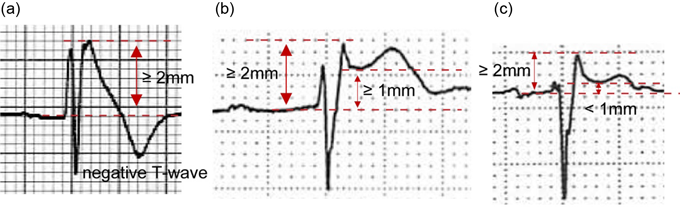

Brugada型心電図の形成と催不整脈性に関しては,右室流出路(RVOT)の貫壁性の活動電位勾配が関与していると考えられている(再分極仮説)3).健常者において,一過性外向きK電流(Ito)の密度は心外膜側のほうが心内膜側よりも高く,第1相notchが心外膜側のほうでわずかに深くなる(Fig. 2a).そして,この傾向はRVOTにおいて特に顕著である.一方,BrS患者の心筋細胞では,遺伝子変異によりNa電流(INa)やCa電流(ICaL)が減少するため,それぞれ活動電位第0相のピーク電位の低下,第2相のplateau相の消失を引き起こし,その結果,心外膜側の第1相notchがより顕著となる(Fig. 2b).このRVOTにおける貫壁性の電位勾配が,右側胸部誘導においてcoved型ST上昇として観察される.また,部位により電位のばらつきが生じ,phase 2 reentryをもとにした心室頻拍・細動を来すと考えられている4).

また,BrS症例の中でも,電気生理学的検査でRVOT心外膜側に異常電位を認める場合,同部位のカテーテルアブレーションによるcoved型ST上昇の正常化と致死性不整脈の抑制効果が報告されており,5年VF-free survival rateは95%と有効な治療法として注目されている5, 6).同部位では,線維化とギャップ結合を形成するconnexin-43 (Cx43)の発現低下を認め,これらが脱分極遅延によるリエントリー回路となって不整脈基質になると提唱されている(脱分極仮説)7).BrSの全ての現象をどちらかの仮説で説明できるわけではなく,現在は,脱分極異常と再分極異常の両者が関与していると考えられている.

BrSは男性優位に発症するが,それには主にテストステロンが関連していると考えられている.BrSと前立腺癌を合併した男性患者において,精巣摘出後にcoved型ST上昇が正常化し8),また,男性BrS患者では健常者と比較して血中テストステロン濃度が高いことが報告されており9),テストステロンはBrSの病態を増悪させる方向に働くと考えられている.テストステロンは,ItoのβサブユニットであるKChIP2の心外膜側での発現量を増加させる.そのため,男性では心外膜側のItoが大きく,活動電位第1相notchの貫壁性電位勾配が大きくなるので,女性と比べてcoved型ST上昇を呈しやすいと考えられている10).

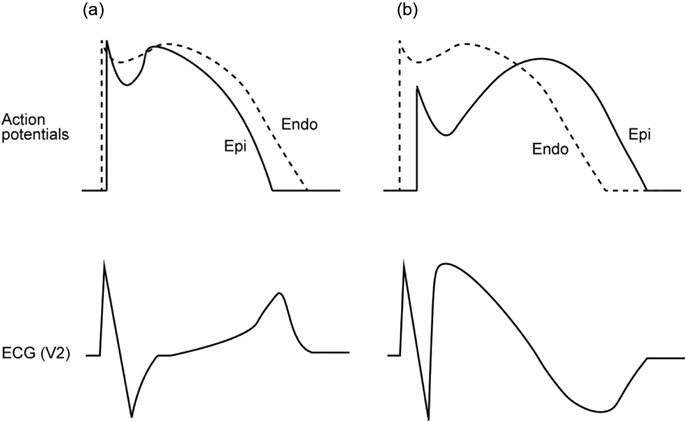

小児例においては,思春期前の時期は,BrSの有病率や致死性不整脈イベント(LAE)頻度には性差がないと報告されている11).その主な原因は,思春期前の男児ではテストステロン分泌量が少ないためと考えられている.しかし,女性BrS患者に着目すると,妊娠中にLAEが減少したり12),閉経以降にLAEが増加するなどの報告があり13),血中エストラジオール値の変化がBrSの病態に影響している可能性も考えられている.我々のグループは,思春期以降の女性BrS患者において,新規発症数とLAE数が減少し,特に一部の女性患者ではcoved型ST上昇が正常化する現象を見いだした(Fig. 3).女性ではテストステロンの血中濃度は一生涯を通してほとんど変化しないため,テストステロンが女性のこのような病態の変化に関与しているとは考えにくく,思春期以降に増加するエストラジオールが保護的に作用しているのではないかと考えている.電気生理学的にも,エストラジオールは,ItoのαサブユニットであるKv4.3の発現を減少させ,Itoを抑制することが報告されており14),Ito抑制によって活動電位第1相notchの貫壁性電位勾配を軽減することで保護的に働いていると推測される.以上より,テストステロンとエストラジオールは,BrSに対して対照的な作用を示すと考えられ,思春期以降の男女差の主要な原因であると考えられる.

遺伝的背景

BrSの原因遺伝子として,最初,心筋NaチャネルαサブユニットであるNaV1.5をコードするSCN5A遺伝子変異が同定され15),現在では20以上の原因遺伝子が報告されている.SCN5Aの機能喪失型変異は,活動電位第0相のINaを抑制することで,第1相notchが顕在化し,貫壁性電位勾配が増強されることで心電図上ではcoved型ST上昇を引き起こす.実際に,SCN5A変異を有する患者では,自然発生型coved型ST上昇を有する割合が高い16).SCN5Aの機能喪失型変異は約15~20%の症例で検出されるが,American College of Medical GeneticsのガイドラインでVUS(病原性不明な変異)として分類されるものもあり,結果の解釈に関して注意が必要である2).一方,BrSの発症には,Gap結合の減少,心筋線維化7),テストステロン8)が関与しているとの報告もあり,BrSは単一遺伝子疾患ではなく,後天的因子を含めた多因子疾患として認識されている.

我が国における多施設共同研究では,SCN5A変異陽性群は陰性群に比べて,初回LAEの発生年齢が有意に低く,LAE頻度が高いと報告されているが17),多くの研究でSCN5A変異は有意なリスク因子として認識されていないため,今後さらなる研究が必要である.小児BrSは成人と比べてSCN5A変異陽性率が高い(25~77%)18–20).小児では,加齢に伴う線維化や性ホルモンの影響が少ないため,相対的に遺伝的影響が強いことが予想される.しかし,SCN5A変異がLAEのリスク因子となるかは成人と同様に議論がある.

SCN5A変異は各種心伝導障害を引き起こし,進行性心臓伝導障害(PCCD)の発症に関連する21).BrS症例でも,SCN5A変異を有する患者では,PR・QRS時間の延長が多い16).SCN5Aヘテロノックアウトマウスの心筋組織では,間質の線維化とCx43の発現異常によるGap結合の錯綜化を認めることから22),これらによって伝導遅延が生じるものと推測される.また,SCN5A変異は,BrS症例において心房性不整脈の合併や心房内伝導時間の遅延とも関連している23).心室と同様に,心房でも線維化やGap結合の異常が伝導遅延を引き起こし,それがリエントリー回路の一部を形成していると考えられている.すなわち,SCN5A変異による伝導障害は,心室筋に限らず,心臓全体に及んでいると考えられる.

疫学

〈成人〉有病率(coved型ST上昇有所見率)は,欧米よりもアジアで高い(0.03%~0.25% vs. 0.05%~0.36%)24).Brugada型心電図出現の平均年齢は45歳,突然死の平均年齢は57歳であり,特に中年期の突然死リスクが高いと考えられている25).LAEによる突然死は,安静時や入眠中,特に夜間0時から6時の間に発生することが多い26).LAEの発生率も欧米よりアジアで高い傾向がある(日本人:2.5%/年,欧米人:1.0%/年)17, 18).また,BrSは男性に多く発症し,男性例が女性例に比べて8~10倍程度多い2).

〈小児〉小児例は比較的少なく,有病率は0.01~0.02%程度と報告されているが27, 28),成人例よりもLAEが多いと報告されている.(2.1%/年vs. 1.0%/年)18).BrSにおいて,発熱はcoved型ST上昇やLAEを誘発させる重要な因子として認識されており29),小児においてLAEの頻度が高いのは,小児の発熱疾患の罹患頻度の高さが一因と考えられている30).そのため,小児BrS患者では,LAE予防のために積極的な解熱剤の使用が勧められる.また,成人例では有病率やLAEの発生頻度に著明な男性優位が見られるが,小児例では性差は見られない11).これは,思春期前の小児では性ホルモンの影響が小さいためと推測されている.小児BrSの人種差に関する報告は少ないが,LAE発生頻度は,我々の小児BrS症例レジストリにおいては5.1%/年と欧米小児例の既報(2.1%/年)よりも高く18),アジア人では欧米人よりLAEを起こしやすい可能性がある.

診断

BrSの現在の標準的な診断は,日本循環器学会のガイドラインやHRS/EHRA/APHRSのexpert consensus statementによるものであり31, 32),心電図所見に基づいて診断される.高位肋間記録を含めた右側胸部誘導の1つ以上に,coved型ST上昇が記録されれば,自然発生型(Fig. 4a),発熱誘発型(Fig. 4b),薬物誘発型(Fig. 4c)いずれでもBrSとして診断される.一方,このようなBrSの心電図診断では偽陽性例が多く見られることが知られており,coved型ST上昇は冠動脈左前下降枝の閉塞で,saddleback型ST上昇は右脚ブロック,左室肥大,漏斗胸,不整脈原性右室心筋症(ARVC)等でも見られる2).そのため,2016年のJ-wave Syndrome Consensus Conferenceにおいて,診断感度を向上させた上海スコアと言われる診断基準が提案された(Table 1)33).心電図所見,臨床所見,家族歴,遺伝学的検査をスコア化し,合計スコアが3.5以上の場合に,probable and/or definite BrSと診断される.この診断基準の特徴は,自然発生coved型ST上昇の重要性は変わらないが,発熱や薬物誘発によるcoved型ST上昇だけではpossibleに留まるようになっている点であり,近年のリスク層別化に関する知見に基づいている.

Table 1 Shanghai criteria| Factors | Points |

|---|

| I. ECG |

| A. Spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern at nominal or high leads | 3.5 |

| B. Fever-induced type 1 Brugada ECG pattern at nominal or high leads | 3 |

| C. Type 2 or 3 Brugada ECG pattern that converts with provocative drug challenge | 2 |

| II. Clinical history |

| A. Unexplained cardiac arrest or documented VF/ polymorphic VT | 3 |

| B. Nocturnal agonal respirations | 2 |

| C. Suspected arrhythmic syncope | 2 |

| D. Syncope of unclear mechanism/ unclear etiology | 1 |

| E. Atrial flutter/ fibrillation in patients <30 years old without alternative etiology | 0.5 |

| III. Family history |

| A. First- or second-degree relative with definite BrS | 2 |

| B. Suspicious SCD (fever, nocturnal, Brugada aggravating drugs) in first- or second-degree relative | 1 |

| C. Unexplained SCD <45 years old in first- or second-degree relative with negative autopsy | 0.5 |

| IV. Genetic test result |

| A. Probable pathogenic mutation in BrS susceptibility gene | 0.5 |

Score (requires at least 1 ECG finding)

≥3.5 points: Probable/definite BrS; 2–3 points: Possible BrS; <2 points: Nondiagnostic

BrS=Brugada syndrome; ECG=electrocardiogram; SCD=sudden cardiac death; VF=ventricular fibrillation; VT=ventricular tachycardia. |

学校心臓検診の一次スクリーニングにおいては,J点で0.2 mV以上のcoved型,saddleback型ST上昇が記録された場合,二次検診へ紹介すべきとしている34).また,二次以降の検診では,12誘導心電図に加え,Holter心電図,運動負荷心電図,Naチャネル遮断薬(ピルジカイニド1 mg/kgを10分かけてiv)を用いた薬物負荷試験,電気生理学的検査等が必要に応じて施行される.ただし,Brugada型心電図には日内変動・日差変動があり,1回の心電図計測だけではBrSを鑑別できないこともあるので注意が必要である.

治療

BrSの突然死予防としてエビデンスが確立されているものは植込み型除細動器(ICD)である.日本循環器学会のガイドラインでは,coved型ST上昇に加えて心肺停止蘇生歴やVF既往を有する場合はクラスI,coved型ST上昇に加えて不整脈原性失神あるいは夜間の苦悶様呼吸を有する,また失神の原因が不明だがEPSでVFが誘発される場合はクラスIIaの推奨度である31).ただし,小児では,体格の変化が早い,活動度が高い,心拍が速いなどの特徴から,リード断線などのデバイス関連合併症や洞性頻脈に対する不適切作動が成人よりも多いことが知られている.皮下植え込み型除細動器(S-ICD)は,小児においてもデバイス関連合併症が少ないとの報告があり35, 36),ペーシングを必要としない場合は検討に値する.S-ICDの植え込みが可能な体格は明確に規定されていないが,日本の多施設研究では,年齢中央値14.0歳(11.0~16.0歳),身長中央値157.0 cm(146.4~165.7 cm),体重中央値46.9 kg(35.8~56.7 kg)の患者に植え込まれている35).また,欧州の多施設研究では,年齢中央値15歳(8~31歳),身長平均値167±12 cm(132~190 cm),体重平均値62±14 kg(30~120 kg)の患者に植え込まれており36),以上を踏まえると,概ね10歳,140 cm,35 kgがS-ICDの植え込みが可能な目安となるかもしれない.

薬物治療はICDに比べてエビデンスレベルが低いが,頻回のVF発作を認める場合にはキニジン予防内服がクラスIIaで,VFストームの急性期治療にはイソプロテレノール静注がクラスIIaで推奨されている.キニジンは,Ia群の抗不整脈薬であるが,INaだけでなく,Itoも阻害するため,第1相の貫壁性勾配が改善することでVFを予防すると考えられている.成人BrSに対するキニジンの用量は300~600 mg/日である31).小児BrSに対するキニジンの用量に関する報告は少なく未確定ではあるが,海外の2つの文献レビューでは,至適用量を15~30 mg/kg/dと30~60 mg/kg/dと記述している37, 38).私たちの小児BrSレジストリーでは,1.7 mg/kg/dと6.0 mg/kg/dの低用量キニジンを投与した2例がLAEにより死亡したのに対し,17~32 mg/kg/dの高用量を投与した4例ではLAEを認めなかったことから,LAEの抑制には比較的高用量のキニジンが必要である可能性が示唆される.ただし,キニジンの投与量を増やすにつれて,光線過敏症や消化器症状などの副反応が増加することが知られており,小児に対するキニジンの至適用量に関するデータ蓄積が望まれる.

カテーテルアブレーションは,薬物抵抗性VFストーム症例やICD適切作動頻発例で推奨される.BrS患者の中でも,電気生理学的検査で右室流出路心外膜側に心室遅延電位や分裂電位を示す症例では,同部位への高周波アブレーションを行うことでcoved型ST上昇が正常化する5).一方,薬物抵抗性VFやVFストームの既往がある重症患者では,心内膜側でも異常電位を認めることがあり,そのうちの約9割で心内膜アブレーションによってVFが誘発されなくなったと報告されている39).また,小児では心外膜アプローチは一般的ではなく,心内膜アプローチが試されることが多い.小児においても心内膜アプローチの成功例が報告されはじめており,成人よりも心筋壁が薄いことが効果的であった要因として考えられている40).

概要

不整脈原性右室心筋症(ARVC)は,右室を中心とした線維脂肪変性と,それによる致死性心室性不整脈と特徴的な心電図所見を来す遺伝性心筋疾患である41).当初は不整脈原性右室心筋異形成(ARVD)と呼ばれていたが,疾患概念の確立とともにARVCという病名に変化してきた.また,近年では左室優位例や両心室で認める例が少なくないことも明らかとなり,より広範な概念として不整脈原性心筋症(ACM)と記載されることもある42).ARVCは比較的若年者に発症し,特にアスリートの突然死の一因とされており,ARVCの可能性がある患者を適切に診断し,管理することが重要である.

病態生理

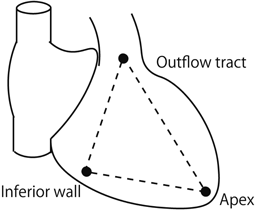

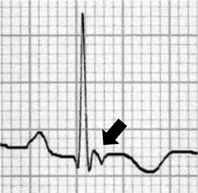

右室における線維脂肪変性は心外膜側から進行し,徐々に貫壁性の病変となり,心筋壁の菲薄化と瘤化を引き起こす.これらの病変は,右室の下壁~心尖部~漏斗部で囲まれた,いわゆるTriangle of dysplasiaで主に見られる(Fig. 5)41).この脂肪線維変性が伝導障害を来した結果,イプシロン波(Fig. 6),右脚ブロック,陰性T波,late potential,リエントリー性心室性不整脈などの特徴的心電図所見を引き起こすと考えられる.また半数以上の症例では,左室の,特に後側壁心外膜下においても病変が見られ,左室由来の各種伝導障害を来すと報告されている43).

ARVCは,1978年にFontaineらにより初めて報告された44).1986年には,ARVCに類似した心臓病変とともに,掌蹠角化症やwooly hairといった皮膚所見を合併したNaxos病が報告され45),デスモソーム蛋白であるPlakoglobinをコードする遺伝子変異がその原因であることが明らかとなった46).それを端緒として,ARVCにもデスモソーム蛋白が関与していることが判明した.

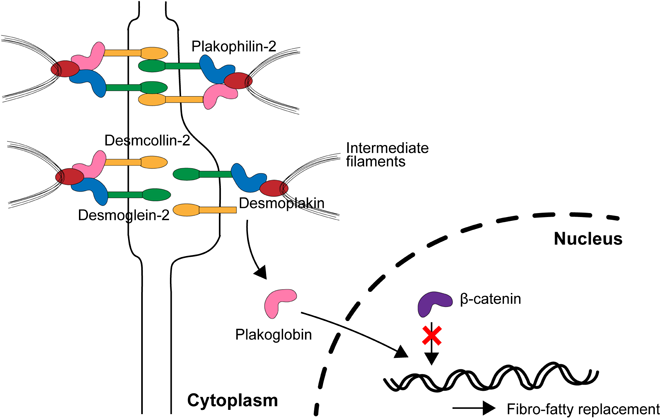

デスモソームは細胞間接着に関わる装置であり,5種類の蛋白質,すなわちPlakoglobin, Desmoplakin,Plakophilin-2,Desmoglein-2,Desmocollin-2によって構成される(Fig. 7).これらのデスモソーム蛋白のいずれかに異常が生じると,細胞間接着が不安定になる.特に,右室自由壁や左室後側壁は機械的ストレスに脆弱な領域であり,運動によって圧負荷がかかることで,細胞間接着が壊れ,細胞死が生じて線維化が起こると考えられている47, 48).そのために,アスリートにおいてARVCによる突然死が多く報告されている.

健常人においては,幹細胞が心筋細胞に分化する過程で,Wnt/β-catenin経路が働いている.心筋細胞にWnt刺激が入ると,β-cateninが核に移行して,PPARγの転写を抑制する.PPARγは間葉系細胞を脂肪へ分化させるのだが,通常β-cateninがブレーキを掛けているので,脂肪ではなく心筋細胞へ分化することができる.一方,ARVCにおいてデスモソーム蛋白のいずれかに異常が生じると,細胞間接着が不安定になり,Plakoglobinが細胞膜付近から細胞質へ遊離する.Plakoglobinは別名γ-cateninと呼ばれ,β-cateninと類似した立体構造を有している.そのため,Plakoglobinが核内に移行すると,β-cateninと競合してPPARγに対するブレーキが効かなくなってしまうため,心筋細胞内で脂肪滴の産生が増加し,脂肪変性が進むと考えられている(Fig. 7)49, 50).

ARVCにおいて心室性不整脈が発生する機序の詳細は明らかではないが,Plakophilin-2の発現を抑制することで,INaやgap結合を構成するCx43が減少することが報告されている51, 52).これらによる伝導遅延がリエントリー回路の基礎となると考えられている.その他,Plakophilin-2ノックアウトマウスでは,Ca2+ハンドリングに関連する複数のタンパク質の発現が減少しており,細胞質内と筋小胞体内のCa2+濃度が上昇することで心室性不整脈が発生することが報告されている53).このような心筋細胞内Ca2+過負荷による催不整脈性の亢進も心室性不整脈の発症に関与している可能性がある.

遺伝的背景

ARVCの主要な原因遺伝子には,5種類のデスモソーム遺伝子と3種類の非デスモソーム遺伝子がある.デスモソーム遺伝子はARVC症例の約60%に検出される54).そのなかでも,Plakophilin-2をコードするPKP2は最も頻度の高い原因遺伝子であり,ヨーロッパでは約半数のARVC患者で検出されるが55),アジアでは約3割とやや少ない56).JUPはARVCの原因遺伝子として初めて報告された遺伝子だが,他の原因遺伝子と比べると頻度はやや少ない57).しかし,それがコードするPlakoglobinはWnt/β-catenin経路と関連していると報告されており,ARVCの発症機序を解明するうえでの鍵となる可能性がある.DSPがコードするDesmoplakinは,細胞膜下に位置するPlakophilin-2やPlakoglobinと接するとともに,細胞内の中間径フィラメントとも接合する(Fig. 7).DSG2とDSC2がそれぞれコードするDesmoglein-2とDesmocollin-2は,細胞膜貫通タンパク質であり,アジア人では,DSG2変異の頻度がヨーロッパ人と比べて高く,DSC2の変異は稀である.デスモソーム蛋白の遺伝子異常は,単一の遺伝子変異よりも複数の遺伝子変異を有する症例のほうが予後不良とされる58).しかし,ARVCの浸透率は低く,同じ遺伝子変異を有する症例間でも表現型が異なることも多いため,診断やリスク層別化における遺伝子変異の有用性については今後の更なる検討が必要である.

ARVCの原因となる非デスモソーム遺伝子には,TMEM43, DES, PLNなどがある59).TMEM43は,Laminと接合して核膜を維持する蛋白質であるTransmembrane protein 43をコードする.ARVCの中でTransmembrane protein 43の変異は稀であるが,同変異は,胎児期にARVCを発症した症例で検出されたとの報告もあり重症である可能性がある60).DESがコードするDesminは心筋細胞内の中間径フィラメントの一つで,その異常によりARVCの他,筋原線維性ミオパシーなども引き起こすとされる61).PLNがコードするPhospholambanは心筋小胞体に位置するCa2+濃度を調節する蛋白質で,その異常によって細胞内Ca2+過負荷を引き起こす62).これらの非デスモソーム遺伝子変異には地域集積性があり,TMEM43変異はカナダのNewfoundlandに,PLN変異はオランダで多く検出される59).

疫学

青壮年期での発症が主で,平均診断年齢は36歳である55).有病率は1,000~5,000人に1人であり,小児の有病率は明らかではないが成人より低いと考えられており,特に12歳以前の発症は稀である42, 63, 64).初発症状としては,動悸,立ちくらみ,失神などが主なものであるが,突然死で初めてARVCの存在に気づかれることもある.既報によれば,7年間のフォロー期間中に,発端者の7割がLAEを経験したのに対し,その家族は8割以上が無症状だったとのことで,浸透率が低いことが示唆される55).心停止時の年齢中央値は25歳であり,若年発症患者ではリスクが高い可能性がある.

男性で有病率や重症度が高いことが報告されており65),性ホルモンや性別による運動強度の違いが関連していると考えられている66, 67).ARVCはアスリートの突然死に隠れていることが知られており,アスリートの突然死症例の13%がARVCであったと報告されている65).これは,強度の高い運動負荷によって機械的ストレスが心臓にかかり,デスモソーム遺伝子の異常などでもともと脆弱であった細胞間接着の破壊が促進されるためであると考えられる.また,20~40代における発症が多いことから,小児においてはリスクを過小評価される傾向があるが,18歳以下のARVC患者を調査した研究では,18歳までに23%の症例がLAEを発症したと報告されている68).小児ARVC患者では,フォロー中の心臓突然死発生割合が成人患者よりも高いとの報告もあるため,より慎重なフォローが必要になる69).

診断

ARVCは2010 revised Task Force Criteria(rTFC)に基づき診断される(Table 2)70).rTFCは,心エコー,心臓MRI(CMR),右室造影等の画像評価,病理所見,12誘導心電図における再分極異常,加算平均心電図のlate potentialを含む脱分極異常,心室性不整脈,家族歴,遺伝子異常といった検査項目をMajorとMinorに分け,総合評価を下す.主に,右室の拡大と収縮不全,右室自由壁組織における線維化,右側胸部誘導における陰性T波とイプシロン波,右室由来の心室頻拍(VT)とPVC,病的遺伝子変異をもとに診断する.

Table 2 Revised Task Force criteria | Major | Minor |

|---|

| 1. Global or reginal dysfunction and structural alteration |

|---|

| Echo | Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm and 1 of the following (end diastole)

a) PLAX RVOT≥32 mm (≥19 mm/m2 BSA)

b) PSAX RVOT≥36 mm (≥21 mm/m2 BSA)

c) Fractional area change ≤33% | Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm and 1 of the following (end diastole)

a) PLAX RVOT≥29 mm to <32 mm (≥16 to <19 mm/m2 BSA)

b) PSAX RVOT≥32 mm to <36 mm (≥18 to <21 mm/m2 BSA)

c) Fractional area change >33 to ≤40% |

| MRI | Regional RV akinesia or dyskinesia or dynssynchronous RV contraction and 1 of the following:

a) Ratio RVEDV/BSA ≥110 mL/m2 (male), ≥100 mL/m2 (female)

b) RVEF ≤40% | Regional RV akinesia or dyskinesia or dynssynchronous RV contraction and 1 of the following:

a) Ratio RVEDV/BSA ≥100 to <100 mL/m2 (male), ≥90 to 100 mL/m2 (female)

b) RVEF >40 to ≤45% |

| RV angiography | Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm | |

| 2. Tissue characterization of wall |

|---|

| Endocardial biopsy showing fibrous replacement of the RV free wall myocardium in≥1 sample, with or without fatty replacement and with: | Residual myocytes <60% by morphometric analysis (or <50% if estimated) | Residual myocytes 60% to 75% by morphometric analysis (or 50% to 65% if estimated) |

| 3. Repolarization abnormalities |

|---|

| ECG | Inverted T waves in right precordial leads (V1, V2, and V3) or beyond in individuals > 14 years of age (in the absence of complete RBBB QRS ≥120 ms) | a) Inverted T waves in leads V1 and V2 in individuals > 14 years of age (in the absence of complete RBBB QRS ≥120 ms) or in V4, V5, or V6

b) Inverted T waves in leads V1, V2, V3, and V4 in individuals > 14 years of age in the presence of complete RBBB |

| 4. Depolarization/conduction abnormalities |

|---|

| ECG | Epsilon wave (reproducible low-amplitude signals between end of QRS complex to onset of the T wave) in the right precordial leads (V1 to V3) | 1. Late potentials by SAECG in≥1 of 3 parameters in the absence of QRS duration of ≥110 ms on the standard ECG

a) fQRS ≧114 ms

b) LAS40 ≧38 µV

c) RMS40 ≦20 µV

2. Terminal activation duration of QRS ≥55 ms measured from the nadir of the S wave to the end of the QRS, including R' in V1, V2, or V3 in the absence of complete RBBB |

| 5. Arrhythmias |

|---|

| ECG and Holter ECG | Non-sustained or sustained VT of LBBB with superior axis (negative or indeteminate QRS in leads II, III, and aVF and positive lead aVL) | 1. Non-sustained or sustained VT or RVOT configuration, LBBB morphology with inferior axis (positive QRS in II, III, and aVF and negative in lead aVL) or of unknown axis

2. > 500 PVC per 24 hours (Holter) |

| 6. Family history |

|---|

| Family history and Genetics | 1. ARVC confirmed in a first-degree relative who meets current Task Force Criteria

2. ARVC confirmed pathologically at autopsy or surgery in a first-degree relative

3. Identification of a pathogenetic mutation categorized as associated or probably associated with ARVC on the patient under evaluation | 1. History of ARVC in a first-degree relative in whom it is not possible or practical to determine whether the family member meets current Task Force Criteria

2. Premature sudden death (<35 years of ag) due to suspected ARVC in a first-degree relative

3. ARVC confirmed pathologically or by current Task Force Criteria in second-degree relative |

Definite: 2 major, OR 1 major and 2 minor, OR 4 minor criteria from different categories

Borderline: 1 major and 1 minor, OR 3 minor criteria from different categories

Possible: 1 major, OR 2 minor criteria from different categories

ARVC=arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; BSA=body surface area; ECG=electrocardiogram; fQRS=filtered QRS duration; LAS40=duration of the low-amplitude signal after the voltage decreased to less than 40 µV; LBBB=left bundle branch block; PLAX=parasternal long axis; PSAX=parasternal short axis; PVC=premature ventricular contraction; RBBB=right bundle branch block; RMS40=root-mean-square voltage of the signal in the last 40 ms; RV=right ventricle; RVEDV=right ventricular end-diastolic volume; RVEF=right ventricular ejection fraction; RVOT=right ventricular outflow tract; VT=ventricular tachycardia. |

小学校1年,中学校1年,高校1年の生徒を対象とした学校心臓検診の一次スクリーニングでは,V1~V3誘導の陰性T波,イプシロン波,左脚ブロック型のVTを認める場合は,二次スクリーニングに紹介することとなっている34).そして,二次スクリーニング以降では,Holter心電図,心エコー,CMR等で精査を行い,確定診断を下す.

しかし,小児におけるARVCの早期診断は成人と比べて困難である.それは,イプシロン波のような特徴的な所見を呈することが少なく71),右側胸部誘導の陰性T波は健常児でも見られるので14歳未満の症例では診断項目としてカウントできないためである70).にもかかわらず,陰性T波はARVC患者で最もよく見られる所見であり,様々な研究結果が報告されている.陰性T波は,主に右側胸部誘導(V1~V3)で観察されるが,前側壁誘導(V4~V6)や下壁誘導(II, III, aVF)など広範囲の誘導で見られるほど,電気生理学的検査における低電位領域が大きく,LAEのリスクが高いと報告されている72).我々のグループは,小児ARVC患者の12誘導心電図と,学校心臓検診で得られた健常児の心電図所見を比較し,小児ARVCの早期診断における陰性T波の有用性に関して検討した.陰性T波が見られる誘導は,健常児では主にIII誘導とV1~V3誘導に限られる一方,ARVC患者では,II, aVF誘導,V3, V4誘導にも見られるなど,より広範な誘導でも認める点に違いが見られた.V4誘導の陰性T波は,小学1年生の健常児でも約1%に見られたが,ARVC患者では50–60%とより高頻度に見られた.以上の所見とガイドラインに基づけば34),II, aVF誘導,V3, V4誘導の陰性T波で,ST接合部下降部の振幅が0.05 mV以上である場合は二次検診を考慮すべきである.

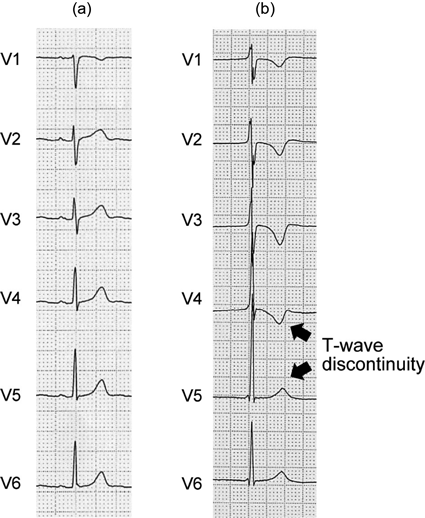

また,LAEを経験したARVC患者は,V4~V5誘導間におけるT波の突然の陽転化(T波不連続性)を示した(Fig. 8)73).小児ARVCでは,広範な誘導の陰性T波やT波不連続性が,早期診断やリスク層別化に有用である可能性がある.

近年,左室優位な症例や両心室に病変を有する症例が注目されており,ARVCからACMへとパラダイムシフトが進みつつある74).既存のrTFCでは左室病変を診断できないため,2020年,左室の収縮能低下,CMRの遅延造影(LGE),V4~V6誘導の陰性T波,低電位のQRS波を含めたPadua criteriaが提唱された(Table 3)75).基本的に,右室病変のみの場合は,rTFCと同様の診断基準であるが,両心室に病変を認める場合は右室と左室いずれかの項目が基準の数を満たせばよい.左室のみに病変を認める場合は,CMRの構造異常(項目2)と病的遺伝子異常を有する場合にACMと診断される.左室病変の多くは非貫壁性の線維脂肪変性による局所的な収縮低下として出現する.そのため,左室拡大は必須の診断項目となっていない.また,左室の心内膜生検は合併症のリスクがやや高いので,代わりにCMRによる診断を用いている点が右室を対象としたrTFCとの違いである.CMRで観察されるLGEはしばしば脂肪浸潤と一致すると報告されている.また,四肢誘導でQRS波が低電位となるのは,線維脂肪変性によって左室心筋容積が減少するためと考えられている.

Table 3 Padua criteria | Right ventricle | Left ventricle |

|---|

| 1. Morpho-functional ventricular abnormalities |

|---|

| Echo, CMR, or angiography | Major

Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or bulging plus one of the following:

1) Global RV dilatation (increase of RVEDV according to the imaging test specific nomograms

2) Global RV systolic dysfunction (reduction of RVEF according to the imaging test specific nomograms)

Minor

Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia or aneurysm of RV free wall | Minor

Global LV systolic dysfunction (depression of LVEF or reduction of echocardiographic global longitudinal strain), with or without LV dilatation (increase of LVEDV according to the imaging test specific nomograms for age, sex, and BSA)

Minor

Regional LV hypokinesia or akinesia of LV free wall, septum, or both |

| 2. Structural myocardial abnormalities |

|---|

| CMR | Major

Transmural LGE (stria pattern) of ≥1 RV region(s) (inlet, outlet, and apex in 2 orthogonal views) | Major

LV LGE (stria pattern) of ≥1 Bull’s Eye segment(s) (in 2 orthogonal views) of the free wall (subepicardial or midmyocardial), septum, or both (excluding septal junctional LGE) |

| Endomyocardial biopsy | Major

Fibrous replacement of the myocardium in ≥1 sample, with or without fatty tissue | |

| 3. Repolarization abnormalities |

|---|

| ECG | Major

Inverted T waves in right precordial leads (V1, V2, and V3) or beyond in individuals with complete pubertal development (in the absence of complete RBBB)

Minor

1) Inverted T waves in leads V1 and V2 in individuals with completed pubertal development (in the absence of complete RBBB)

2) Inverted T waves in leads V1, V2, V3, and V4 in individuals with completed pubertal development in the presence of complete RBBB | Minor

Inverted T waves in left precordial leads (V4–V6) (in the absence of complete LBBB) |

| 4. Depolarization abnormalities |

|---|

| ECG | Minor

1) Epsilon wave (reproducible low-amplitude signals between end of QRS complex to onset of the T wave) in the right ventricular leads (V1 to V3)

2) Terminal activation duration of QRS ≥55 ms measured from the nadir of the S wave to the end of the QRS, including R′, in V1, V2, or V3 (in the absence of complete RBBB) | Minor

Low QRS voltages (<0.5 mV peak to peak) in limb leads (in the absence of obesity, emphysema, or pericardial effusion) |

| 5. Ventricular arrhythmias |

|---|

| ECG, Holter ECG | Major

Frequent PVC >500/24hr, non-sustained or sustained VT of LBBB morphology

Minor

Frequent PVC >500/24hr, non-sustained or sustained VT of LBBB morphology with inferior axis (“RVOT pattern”) | Minor

Frequent PVC >500/24hr, non-sustained or sustained VT with a RBBB morphology (excluding “fascicular pattern”) |

| 6. Family history |

|---|

| Family history/ genetics | Major

1) ACM confirmed in a first-degree relative who meets diagnostic criteria

2) ACM confirmed pathologically at autopsy or surgery in a first-degree relative

3) Identification of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic ACM mutation n the patient under evaluation

Minor

1) History of ACM in a first-degree relative in whom it is not possible or practical to determine whether the family member meets diagnostic criteria

2) Premature sudden death (<35 years of age) due to suspected ACM in a first-degree relative

3) AM confirmed pathologically or by diagnostic criteria in a second-degree relative |

| ACM=arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; BSA=body surface area; CMR=cardiovascular magnetic resonance; ECG=electrocardiogram; LBBB=left bundle branch block; LGE=late gadolinium enhancement; LV=left ventricle; LVEDV=left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; PVC=premature ventricular contraction; RBBB=right bundle branch block; RV=right ventricl; RVEDV=right ventricular end-diastolic volumee; RVEF=right ventricular ejection fraction; RVOT=right ventricular outflow tract; VT=ventricular tachycardia. |

治療

ARVCの治療としては,心室性不整脈と心不全に対する治療がある76).日本循環器学会のガイドラインでは,心停止,VF,血行動態が不安定なVTの既往を有する症例や,重度の右室または左室の収縮能低下を有する症例に対しては,植え込み型除細動器(ICD)移植術が推奨される(class I)77).

抗不整脈治療としてICDを留置できない症例ではβ遮断薬が,頻回のICD作動がある症例ではアミオダロンやソタロールが用いられる76).これらの薬物治療が無効な場合,カテーテルアブレーションが選択されることもあるが,これ自体で不整脈器質が治癒する訳ではなく,不整脈の発生数を軽減することでQOLを高める意味合いがある.

右心不全を有する症例では,前負荷を軽減する目的で硝酸イソソルビドを使用することがある76).また,有症候性の心不全を有する症例には,アンギオテンシン変換酵素阻害薬,アンギオテンシン受容体拮抗薬,β遮断薬等が推奨される.心室瘤を有する症例では,抗血栓療法が併用される.

ARVCはアスリートの中にも隠れているが,運動強度に応じて進行の早さが異なり67),運動に伴うカテコラミン増加は心室性不整脈を誘発することがわかっている78).動物実験でも,運動負荷を行ったJUPノックアウトマウスでは,野生型と比べて右室拡大と右室起源VTが増加したと報告されている79).これらの知見は,ARVC患者における運動制限の必要性を示唆しており,我が国のガイドラインでは,ARVCと診断された症例の管理指導区分はCで,軽いものを除いて運動は禁忌となっており,1~3カ月おきにリスク評価の検査を繰り返すべきとされている34).一方,2019 HRS expert consensus statementでは,病的遺伝子変異が陽性でさえあれば,ARVCの診断基準を満たさなくても,競技スポーツや持久的なスポーツを避けるべきとしている76).具体例としては,フィギュアスケート,短距離・長距離走,バレーボール,バスケットボール,サッカーなどが挙げられている.