1. 学校管理下突然死の定義

WHO(世界保健機構)では,発症から24時間以内の予期せぬ内因性(疾病による)死亡とされている.共済給付制度上では,通常は発症から24時間以内に死亡したものとするが,救急医療の進歩もあり,意識不明等のまま発症から相当期間を経て死亡に至ったものを含めており,その判定は災害共済給付審査委員会で行っている.

2. 突然死の発生数

JSCの集計に基づき,1983年から2013年までの学校管理下における死亡事例数をグラフに示した1)(Fig. 1).年間の総死亡数とその中で突然死に分類される事例数は,80年代にはそれぞれ約250件と約120件あったが,最近の2005年以降はそれぞれ約75例と約40例に減少している.少子化による加入者減少の影響を補正するため,突然死全体と,その中で心疾患が原因と考えられる心臓系突然死(Sudden Cardiac Death: SCD)の生徒10万人あたりの年間発生率をFig. 2に示した.1980年代から2010年代までに,突然死全体の発生率は約0.6(/10万生徒・年;以下,発生率の単位は同じ)から約0.2へ,SCD発生率は約0.4から約0.1へと減少した.1980年代から2000年代前半までは,SCDは突然死全体の7~8割を占めていたが,2007年頃から4~6割程度にその比率が減少した.図中の矢印で時期を示した1995年の学校心臓検診における心電図の義務化は,すでに多くの地域で心電図が行われていたこともあり,影響は小さかったと思われる一方で,2005年以降に学校教員によるAEDの使用が可能になったことは,心臓系突然死の減少に大きく寄与したと思われる.

3. 発生率の国際比較

SCD発生率を国際的に評価することも必要である.報告は限られており,調査方法の違いや,対象に先天性心疾患や心筋症など危険性の高い生徒も含まれているかどうかという点や,学校管理下など調査対象とする年齢層の違いなどにより正確な比較が困難ではある.最近の全米50州の高校生での突然の心停止(sudden cardiac arrest: SCA)またはSCDに対するAED使用調査に基づく報告2)によると母集団は約8分の1であるが,2年間で高校生におけるSCAの発生率は0.63(約207万人中26名),SCDはstudent athletesとnon-athletesに各2名ずつで発生率はそれぞれ0.13,0.08(/10万生徒・年)とされ,non-athletesと我々のデータがほぼ同等の値であると考える.またSCA発生率は,SCA全体と比べてathleteで約2倍(1.14),non-athleteで約1/2(0.31),男子では約3倍(1.73),女子では約1/2(0.31)であった.

SCAについて他の報告では母集団の違いによりデータは様々に分散しており,SeattleのLotfiら3)は,2005年までの16年間の大学生まで含めた学校での頻度は0.18で,教職員など学校での成人のSCAの頻度4.51に比べ25分の1程度であったと報告している.また,イスラエルで10~44歳の心電図スクリーニングを行ったathletesでは2.66)と報告されている.

SCDは1983~93年における高校生のathletesでは男子0.75,女子0.13と性差が明らか5)と報告された.Minnesota州の調査では,ほぼ同時期(1985~96年)にMaronら6)は3例の男子のSCDで0.46,その後の調査でトレーニング前に病歴聴取と診察を行うと0.24から0.11まで減少している7)が,必ずしも検診スクリーニングを肯定はしていない.

イタリアのVeneto市におけるCorradoらの長期(1979~99年)のSCDの調査報告8)ではathletesで2.3,non-athletesは0.9であった.Corradoらはさらに1982年から病歴,診察,心電図によるスクリーニングを加えた結果,athletesでは1979~80年の3.6から2003~04年には0.4に減少したことも報告9)している.

2000年以降にはAEDや蘇生に関する記述が増えてくるが,2004~08年のNCAAデータベースによる大学生athletesでは2.310),1998~2012年の消防庁データでは18~24歳のSCDは,学校管理外も含むため3.811)とToresdahlや筆者の調査よりかなり多い.欧州ではフランスの10~35歳の前方視的SCD全国調査12)で0.46,デンマークで2000~06年の12~35歳のスポーツ関連SCDが1.2という報告13)があり,米国も含めて学校における突然死の減少を記載した報告が今後明らかにされることを期待したい.

4. 学校における救命活動の普及

2000年から日本蘇生協議会(JRC)がInternational Liaison Committee on Resuscitation: ILCOR)に参画し推進されてきた,AEDを含む救命活動の講習は,2004年に救急救命士の気道確保が可能となり,2005年には非医療従事者のAED使用が可能になった.それに伴い学校現場でも蘇生活動とAED使用が行われ始めたという情報が増えた.そのため2012年の時点で,JSCの学校事故災害報告書について2005年以降のAEDの使用報告を抽出し,集計した結果をFig. 3に示した14).学校現場においては,2007年からは救急隊以前に教職員がより多くAEDを使用開始していることが示された.

また,2013年の文部科学省報告15)では,年々小中高等学校でのAED設置率は上昇し,Table 1に示すように90%以上の学校でAEDが設置されるようになり,そのほとんどで教職員への講習,トレーニングが行われている.また,最近推進される中学,高校の生徒へのBLS,AED講習もそれぞれ65%,75%の学校で行われていると報告されている.また2013年に日本学校保健会で行った学校における蘇生とAED使用に関する全国調査16)では,5年間で690例の心肺蘇生が行われ,522例でAEDが使用されたと報告され,JSCのデータより実際には多くの例で行われている可能性がある.

Table 1 2013 Survey of basic life support and automated external defibrillators in schools by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology |

| The ratios of schools that are planning to equip with, or are performing maintenance of, automated external defibrillators (AEDs) are more than 90%. Approximately 90% of schools are training teachers in Basic Life Support (BSL) and AED. Recently, students have been learning BSL and AED in approximately 70% of junior and senior high schools. |

JCSのデータについて,AEDの使用が一般化したと考えられる2008年から2013年までの学校管理下でSCD事例と救命活動により蘇生されたSCA事例とを調査した.2008年からの6年間にJSCに報告された死亡事例の報告書を確認し,外因性の可能性が否定され,心疾患との関連が強く考えられる121事例をSCDとした.一方,調査期間中の全報告事例に対して,Table 2に示したように,‘AED’,‘ICD’,‘植え込み’,‘除細動’,‘心室細動’,‘心筋症’,‘胸骨圧迫’,‘蘇生’,‘心臓マッサージ’の9つのkeywordsによる検索を行い478事例が抽出された.これらのうち,重複例141,死亡例16,保育所幼稚園30,外因性66,中枢神経疾患12,熱中症6を除外した結果,207例が救命された群として抽出された.これらのSCDと救命されたSCA事例を集計,分析した.

Table 2 Keyword search for resuscitated cases (2008–2013) |

| Resuscitated cases were extracted from all school reports by keyword search. The nine keywords and the number of cases including those words are shown in the slide as original Japanese words and “translation in English.” Each keyword was extracted from a few or many cases. We examined these, and data mining was done for these exclusion criteria. In the end, 207 cases were listed as resuscitations from sudden cardiac arrest in schools. |

1. SCDの発生頻度年次推移

Fig. 4に示すように,発生数と発生率は,2008年からそれぞれ年間12~30件,0.1~0.17の間で推移し,直近2年間はそれぞれ15件以下,0.1以下に減少傾向が見られた.0.1以下のSCD発生率は前述のToresdahlらの集計2)と比較するとnon-athletesのレベルに近い.

2. SCAの発生頻度年次推移

SCAのうち救命活動によって蘇生されたと判断した事例数は,2008年以降年間26~39件であり,SCDと合わせて年間のSCA発生率は0.24~0.39であった.これは,2005年以前のSCDの発生率と同レベルであることがFig. 2からわかる.

さらに,SCA全体に対する蘇生成功件数の比率(図中のR/(R+D))は,Fig. 4に示すように,年間10万対0.3~0.4発生するSCAのうち55~70台に達しており,直近の2年間は成功率70%を超えていると推測される.

総務省による日本の一般社会での最新のデータ17)では,2014年に目撃者のあった心原性心肺停止は25,255件あり,bystanderによる応急手当は13,679人(54.2%),1か月後の生存は2,106人(15.4%)とされており,学校教職員の救急対応は効果を挙げていると思われる.

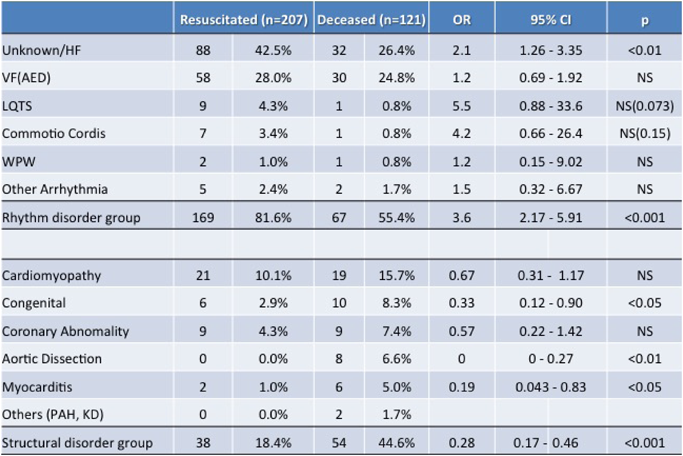

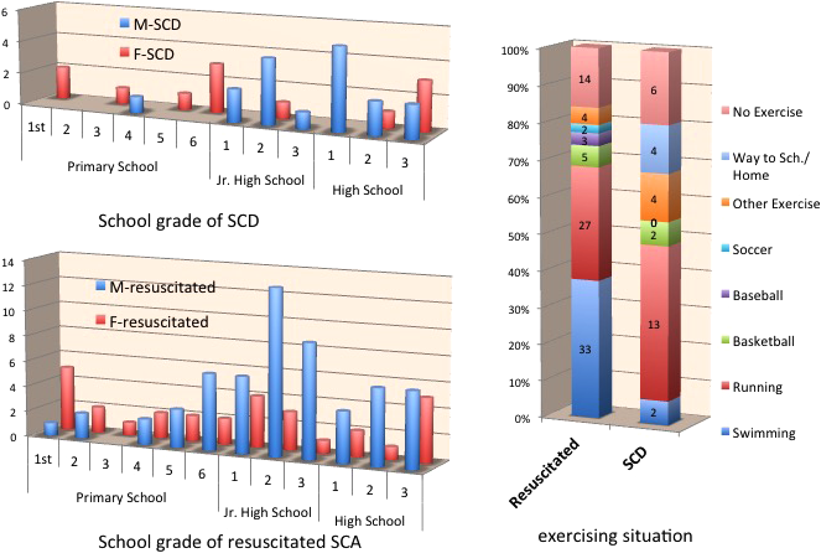

3. SCDの原因疾患(Fig. 5)

突然死した事例の原因疾患の判断は必ずしも容易ではないが,2008年から6年間の「心臓系」および「大血管系その他」の突然死について,原因疾患を推定した.報告書の中に,死亡する可能性がある疾患や健康診断所見の記載がある場合にはその心疾患を原因とした.それ以外のいわゆるunexpected sudden deathでは,一部で剖検報告書の結果から原因を推定できたが,剖検後も原因が不明な例が少なからず存在した.また,「急性心不全」と記載される例は現在でも少なからずあり,その原因がいずれの報告書からも明らかでない場合は原因不明に分類した.また,心停止事例発生後,AEDが装着され作動したことが明記されている事例は,pulseless VTが含まれている可能性はあるが,心室細動(VF)に分類した.

対象としたSCD事例は121例あり,そのうちFig. 5に示すように,死亡診断書上の「急性心不全」を含む原因不明例が32例(26%)と最も多く,次にVFが30例(25%),心筋症が19例(16%)(肥大型15例,拡張型2例,拘束型1例,左室心筋緻密化障害1例,不整脈源性右室心筋症:ARVC1例),先天性心疾患が10例(未手術1例:大動脈弁上部狭窄(Williams症候群),手術後9例:大動脈弁狭窄兼閉鎖不全に対する弁置換術後,房室中隔欠損症術後,修正大血管転位術後2例,肺動脈閉鎖+単心室2例,両大血管右室起始症ペースメーカー装着後,心室中隔欠損及び大動脈弁閉鎖不全弁置換術後,大動脈縮窄複合術後)(8%),冠動脈疾患9例(起始異常5例,低形成2例,機序不明の虚血2例)(7%),大動脈解離8例(6%),急性心筋炎6例(5%)の他に,QT延長症候群(LQTS),WPW症候群,心臓震盪,肺動脈性肺高血圧症,川崎病の既往,不完全右脚ブロック,心房期外収縮が各1例であった.

4. 蘇生されたSCAの原因疾患(Fig. 6)

SCAの中で蘇生された事例では死亡診断書や死体検案書がなく,病院での過料もそれほど医療費を要しなかった場合には報告書の内容も限定されてくるが,多くはSCDと同様にすべての関連する報告書から情報を集め,心停止を発症する可能性がある疾患の記載がある場合にはそれを原因とした.

調査期間に対象としたSCA 207例のうち,Fig. 6に示すように,88例(43%)と半数近くが原因不明であった.次いでVFが58例(28%),心筋症が21例(10%)(肥大型17例,拡張型,拘束型,左室心筋緻密化障害,不整脈源性右室心筋症:各1例),LQTS 9例(4%),冠動脈疾患9例(急性心筋梗塞6例,冠攣縮性狭心症2例,左冠動脈肺動脈起始症1例)(4%),先天性心疾患6例(未手術2例:大動脈弁狭窄,術後4例:修正大血管転位術後,大動脈弁置換術後,肺動脈閉鎖,心室中隔欠損術後)(3%),心臓震盪7例(3%),急性心筋炎2例(1%),WPW症候群2例(1%),その他の不整脈5例(Brugada症候群:BrS,カテコラミン誘発性心室頻拍(CPVT),洞機能不全症候群,心室頻拍,原疾患不明のICD装着例各1例)であった.

これらの結果から,これまで学校心臓検診で,突然死の可能性があるとして抽出され,管理方法に議論が続けられてきたLQTS,WPW症候群については,突然死は6年間で各1例に減少したことが注目される.同期間にSCAを発症していたが蘇生された例は,LQTSが9例あったのに対し,WPW症候群は2例のみであった.おそらくWPW症候群は小児期にもリスクのある例に対してカテーテルアブレーションによる治療が普及してきたのではないかと思われる.LQTSなど致死的不整脈では心停止がこれまで同様に一定頻度で発症しているが,学校現場での救急蘇生処置が効果をあげている可能性が高いと思われる.

救急蘇生の実践は,不整脈系の疾患で成功例が多いと予想されるため,次にSCA蘇生成功例とSCD例について,原因を不整脈及び心電図異常群と,器質的疾患群に分けて蘇生成功実績を比較した.

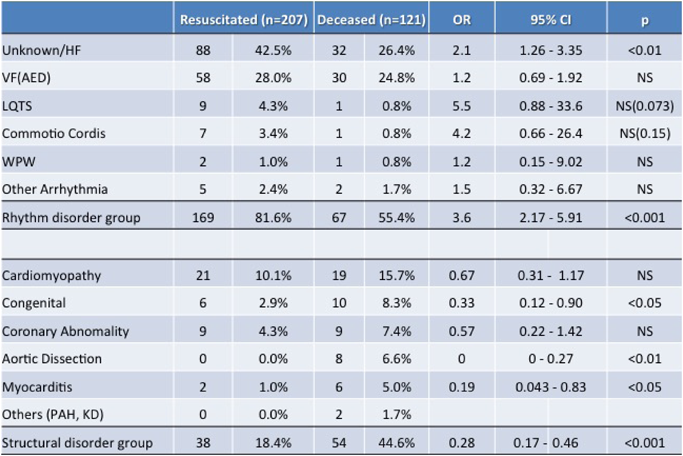

5. 各原因疾患の蘇生効果の比較

3,4で述べた原因不明例,心室細動,LQTS,WPW,その他の不整脈を不整脈群(Rhythm disorder: R群)とし,心筋症,先天性心疾患,冠動脈疾患,大動脈解離,急性心筋炎を器質的疾患群(Structural disorder: S群)とした.

各原因及び両群について,蘇生成功例と突然死例のそれぞれ全体における比率と,蘇生成功の実績から算出したOdds比(OR)をTable 3にまとめた.R群では何の疾患分類もORが大きく,R群全体と原因不明あるいは急性心不全を原因とした事例はそれぞれp<0.001,p<0.01のレベルで蘇生成功例が多かった.また,全体に対して事例数が少ないため有意ではなかったが,LQTS,心臓震盪はORが各5.5,4.2と大きく,学校での心停止において,蘇生される可能性が高い疾患であるといえる.逆にS群の疾患及び群全体はいずれもORは小さく,心筋症,先天性心疾患,大動脈解離,急性心筋炎では有意に蘇生成功の可能性が低いと考えられた.冠動脈疾患は,SCDでの報告書からは,原因に先天性の起始異常5例と低形成2例が剖検によって判明していたが,2例は動脈硬化の所見であった.蘇生されたSCA群の報告書では先天異常の有無は左冠動脈肺動脈起始症(ALCAPA)1例のみ記載されており,他は心筋梗塞とされるも原因は明確でなかった.冠動脈の先天異常は運動負荷によって虚血が顕性化し,心停止に至るが,安静時心電図でのスクリーニングは困難で「予期せぬ運動関連突然死」の代表的な原因であることへの注意をMaronら18)がACC,AHA合同のcouncilから提言している.施設によっては,これを積極的にMRIで発見する試みも計画されている19).

Table 3 Cause and outcome of cardiac arrest in schools (2008–2013) |

| From the data on cause of sudden cardiac death and resuscitated sudden cardiac arrest, we analyzed the odds ratios for resuscitation according to each cause. Long QT had the highest odds ratio (OR), at 5.5, followed by commotio cordis, at 4.2. The rhythm disorder group had a significant high OR at 3.4 (p<0.001). In contrast, aortic dissection did not have a resuscitated case, and myocarditis had an OR of 0.19, signifying smaller possibility of resuscitation. Cardiomyopathy, congenital coronary abnormality, and congenital structural heart disease also had low ORs; however, they were not significantly different from 1. The structural disorder group had a significantly low OR, at 0.28 (p<0.001). OR, odds ratio; CI, confidential interval; PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; KD, past history of Kawasaki disease. |

6. 原因不明突然死例への対応

原因不明に分類した事例の発症状況について分析すると,Fig. 7に示すように,小学生の女児での発症が比較的多く見られており,特に蘇生されたSCAで水泳中の発症が多く見られることから,この中にはLQTSを代表とする遺伝性不整脈が少なからず含まれていると推測される.一方中学生以上の運動関連の事例も多いことや,監察医制度が一部の自治体のみに限られている現状から,原因不明とされる中に,器質的疾患も含めて,まだ多くの病態が混在している可能性がある.現行の学校心臓検診で発見できない疾患が解剖で判明することもあり,剖検で発見されやすい疾患に焦点を当てて検診方法を見直す必要もあろう.

デンマークでの1~18歳小児のSCD114例中77%に剖検を行ったデータでは,約半数が遺伝性の不整脈ではないかと推測されており20),オランダの50歳以下での予期せぬ突然死140例の血縁者からの診断では,はLQTSが19%,CPVTが17%,BrSが15%,ARVCが13%の順21)であり,SCA蘇生例69例の前者では肥大型心筋症(HCM)が17%,心筋梗塞14%,LQTS,BrS,ARVCはいずれも12%の順で多かったが,CPVTは2%と少なく,不整脈性疾患の中で救命率が低い可能性がうかがわれる.

SCA事例に対する遺伝子検索は,日本では現時点では病院,主治医の判断や一部の研究者に依存しており,突然死の原因究明と予防のための策定はされておらず,積極的な検討が必要と思われる.

1. 中枢神経系突然死

学校管理下すなわち就学年齢での突然死の原因として,心疾患以外に中枢神経系疾患によるものがあり,以前から毎年10例前後発生している.心疾患同様に報告書の調査によると,主な原因疾患としては,脳内出血やくも膜下出血,脳梗塞,てんかん発作などである(Fig. 8).心疾患での突然死が年間20例前後に減少してきたため,神経疾患が原因となる比率は増加しており,予防可能か検討が必要と思われる.出血性疾患が半数以上を占めており,JSCの報告書からは脳内出血,くも膜下出血などの記載にとどまるが,文献的には突然死の原因には脳血管の動静脈奇形,動脈瘤を含む先天異常22, 23),発見されていない脳腫瘍24)や血管炎25)が潜在している場合もあるとされる.幼児期の意識消失発作を「てんかん」と診断されてきた例が,学校管理下での発症後にLQTSと診断された事例はしばしば経験される.痙攣に伴う自律神経の変調は不整脈発症につながるため,てんかんと言われる児で発汗,さむけ,めまいなど体調の変化が見られる場合には注意を要する26).てんかん小児での突然死例では,MRIで計測した灰白質量が,扁桃体−海馬周囲で減少し,視床周囲で増加しているとする研究がある27).またKCNQ1変異の家系の中には,続発する病態とは別にてんかんとLQTSとを合併している例もあるとする報告もある28).難治性痙攣疾患の中で,乳児重症ミオクロニーてんかん(Dravet症候群)はしばしば突然死がある.興奮性神経細胞で産生するNaイオンチャネル蛋白Nav1.1合成に関連するSCN1A遺伝子変異が判明しており29–35),発達障害が比較的軽症の場合には就学している児もあり,注意を要する.

また,学校での事例は明らかでないが,軽症でも抗てんかん薬Lamotrigine36),ADHD治療薬atomoxetine37),向精神薬Imipramin38)などの投与がマクロライド系抗菌薬39, 40)と同様に薬剤性のLQTS発症の可能性にも注意する必要がある.

2. 就学前(乳幼児)の突然死

JSCでは,就学前施設(保育園,幼稚園,保育所)における乳幼児の突然死についても申請と報告書が提出されているが,災害給付制度への加入率が約80%と就学年齢よりも低く,心臓検診が行われていない年齢であり,心疾患についての情報は少ない.2008~13年における突然死事例は計26例で男児が15例(57.7%)であった.事例発生数は1999~2008年の10年間で40例1)であり,平成10年からのうつぶせ寝への警告キャンペーン以降減少した41)が,その後,厚生労働省の統計では,全国でSIDSは年間100~150例であまり明らかな減少はない42).年齢は0歳5例,1歳11例,2歳5例,3歳2例,4歳2例,5歳1例で,21例(80.8%)が午睡中や終了時に気づかれたと報告されており,活動中は少ないことが特徴である.先行する発熱を3名(11.5%)に認めた.診断は,乳幼児突然死症候群(Sudden Infantile Death Syndrome: SIDS)とされる例が11例(42.3%),不詳と記載される例が10例(37.4%),他は肥大型心筋症,急性心筋炎,嘔吐後心肺停止,頭蓋内出血,溺水が各1例であった.AEDが使用された記載があるのは4例(15.4%)で,使用頻度はまだ少ない.致死的不整脈の関与も少なからずあると考えられるが,この年齢では感染症や代謝異常症,難治性痙攣なども多いとされ,正確な頻度が不明である.SIDS症例だけでなく,乳幼児突発性危急事態(apparent life threatening events; ALTE)を含めて,本人及び1親等血縁者の遺伝学的検索により,致死的不整脈のみならず代謝疾患43)や睡眠中のセロトニン転送経路異常の関与44)などの病態解明が可能になりつつあり,日本でも積極的に実施できる体制構築が望まれる.

一方,救命処置の普及に関する最近の調査研究では,国内の乳幼児施設での小児一次救命処置講習の受講経験は51.9%45),AED設置率に関する幼稚園の約50%,認可保育所の約25%46)に過ぎない.乳幼児でのBLSトレーニングとAED設置の効果は未知数ともされる47)が,午睡中の身体反応の解明に加え,幼稚園,保育所での心電図検診や乳児の蘇生法とAED普及を改善する検討は有意義と思われる.

積極的な蘇生行動を呼び掛けるにあたり,欧米大多数の地域では,非医療従事者が緊急時に蘇生行動を行った場合に,結果を問われないとする「善きサマリア人の法(Good Samaritan laws)」が法整備され,医療者についても航空機内の場合や,医学生の場合についての細則まで検討48–50)されつつある.日本ではまだ法整備の動きも不明確であり,検討が必要と思われる.

3. 蘇生成功事例の二次再発予防

除細動によるSCAからの回復症例の中には,その後に再発予防のためICD(Implantable cardioverter defibrillator:植込み型除細動器)を挿入して,再発作時の対応が可能になった報告もあり,予測し得なかった突然死が救命され,予防も可能な状態にできる時代になったことを象徴している51–54).このような生徒たちへの医療関係者や学校関係者の対応,管理方法についての問題点は,今後まとめられていく必要があると思われる.

引用文献References

1) 鮎沢 衛,伊東三吾,岡田和夫,ほか:学校における突然死予防必携 改訂(第2版).独立行政法人日本スポーツ振興センター学校安全部安全情報課2010. pp. 16–21‹http://www.jpnsport.go.jp/anzen/Portals/0/anzen/kenko/jyouhou/pdf/totsuzenshi/22/totsuzenshi22_2_1.pdf›

2) Toresdahl BG, Rao AL, Harmon KG, et al: Incidence of sudden cardiac arrest in high school student athletes on school campus. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11: 1190–1194

3) Lotfi K, White L, Rea T, et al: Cardiac arrest in schools. Circulation 2007; 116: 1374–1379

4) Steinvil A, Chundadze T, Zeltser D, et al: Mandatory electrocardiographic screening of athletes to reduce their risk for sudden death proven fact or wishful thinking? J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 1291–1296

5) Van Camp SP, Bloor CM, Mueller FO, et al: Nontraumatic sports death in high school and college athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995; 27: 641–647

6) Maron BJ, Gohman TE, Aeppli D: Prevalence of sudden cardiac death during competitive sports activities in minnesota high school athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32: 1881–1884

7) Roberts WO, Stovitz SD: Incidence of sudden cardiac death in Minnesota high school athletes 1993–2012 screened with a standardized pre-participation evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: 1298–1301

8) Corrado D, Basso C, Rizzoli G, et al: Does sports activity enhance the risk of sudden death in adolescents and young adults? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 1959–1963

9) Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, et al: Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA 2006; 296: 1593–1601

10) Harmon KG, Asif IM, Klossner D, et al: Incidence of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes. Circulation 2011; 123: 1594–1600

11) Farioli A, Christophi CA, Quarta CC, et al: Incidence of sudden cardiac death in a young active population. J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4: e001818

12) Marijon E, Tafflet M, Celermajer DS, et al: Sports-related sudden death in the general population. Circulation 2011; 124: 672–681

13) Holst AG, Winkel BG, Theilade J, et al: Incidence and etiology of sports-related sudden cardiac death in denmark: Implications for preparticipation screening. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7: 1365–1371

14) 加藤雅崇,鮎沢 衛,住友直方,ほか:【学校での心事故はふせげるか】AEDの現況.小児科2013; 54: 277–283

15) 文部科学省.学校健康教育行政の推進に関する取組状況調査(平成25年度実績),p. 6. ‹http://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2015/04/01/1289307_10.pdf›

16) 日本学校保健会「平成25年度学校生活における健康管理に関する調査」(2013年),p. 15. ‹http://www.gakkohoken.jp/book/ebook/ebook_H260030/H260030.pdf›

17) 総務省消防庁:平成27年版 救急・救助の現状,p. 46. ‹http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/kyukyukyujo_genkyo/h27/01_kyukyu.pdf›

18) Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Kligfield P, et al: Assessment of the 12-lead electrocardiogram as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12–25 years of age): A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64: 1479–1514

19) Angelini P, Vidovich MI, Lawless CE, et al: Preventing sudden cardiac death in athletes in search of evidence-based, cost-effective screening. Tex Heart Inst J 2013; 40: 148–155

20) Winkel BG, Risgaard B, Sadjadieh G, et al: Sudden cardiac death in children (1–18 years): symptoms and causes of death in a nationwide setting. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 868–875

21) Van der Werf C, Hofman N, Tan HL, et al: Diagnostic yield in sudden unexplained death and aborted cardiac arrest in the young: The experience of a tertiary referral center in The Netherlands. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7: 1383–1389

22) Plunkett J: Sudden death in an infant caused by rupture of a basilar artery aneurysm. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1999; 20: 211–214

23) Cioca A, Gheban D, Perju-Dumbrava D, et al: Sudden death from ruptured choroid plexus arteriovenous malformation. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2014; 35: 100–102

24) Byard RW, Bourne AJ, Hanieh A: Sudden and unexpected death due to hemorrhage from occult central nervous system lesions: A pediatric autopsy study. Pediatr Neurosurg 1991–1992; 17: 88–94

25) Pistracher K, Gellner V, Riegler S, et al: Cerebral haemorrhage in the presence of primary childhood central nervous system vasculitis: A review. Childs Nerv Syst 2012; 28: 1141–1148

26) Moseley BD: Seizure-related autonomic changes in children. J Clin Neurophysiol 2015; 32: 5–9

27) Wandschneider B, Koepp M, Scott C, et al: Structural imaging biomarkers of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Brain 2015; 138: 2907–2919

28) Tiron C, Campuzano O, Pérez-Serra A, et al: Further evidence of the association between LQT syndrome and epilepsy in a family with KCNQ1 pathogenic variant. Seizure 2015; 25: 65–67

29) Hirose S, Scheffer IE, Marini C, et al: SCN1A testing for epilepsy: Application in clinical practice. Epilepsia 2013; 54: 946–952

30) Glasscock E: Genomic biomarkers of SUDEP in brain and heart. Epilepsy Behav 2014; 38: 172–179

31) Cheah CS, Westenbroek RE, Roden WH, et al: Correlations in timing of sodium channel expression, epilepsy, and sudden death in Dravet syndrome. Channels (Austin) 2013; 7: 468–472

32) Ogiwara I, Iwasato T, Miyamoto H, et al: Nav1.1 haploinsufficiency in excitatory neurons ameliorates seizure-associated sudden death in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 2013; 22: 4784–4804

33) Kalume F: Sudden unexpected death in Dravet syndrome: Respiratory and other physiological dysfunctions. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2013; 189: 324–328

34) Kalume F, Westenbroek RE, Cheah CS, et al: Sudden unexpected death in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 1798–1808

35) Berkovic SF, Harkin L, McMahon JM, et al: De-novo mutations of the sodium channel gene SCN1A in alleged vaccine encephalopathy: A retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 488–492

36) Verma DMA, Kumar A: Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: Some approaches to prevent it. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015; 27: e28–e31 (doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13120366)

37) Sawant S, Daviss SR: Seizures and prolonged QTc with atomoxetine overdose. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 757

38) Dodd S: QT Alterations in psychopharmacology: Proven candidates and suspects. Curr Drug Saf 2010; 5: 97–104 ‹http://www.eurekaselect.com/70539/article#sthash.A5MSn0dx.ddf›

39) Germanakis I, Galanakis E, Parthenakis F, et al: Clarithromycin treatment and QT prolongation in childhood. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95: 1694–1696

40) Tay KY, Ewald MB, Bourgeois FT: Use of QT-prolonging medications in US emergency departments, 1995–2009. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014; 23: 9–17

41) 田中哲郎,石井博子,内山有子:乳幼児突然死症候群の発生率と疫学的特徴の推移.日本小児救急医学会雑誌2009; 8: 8–15

42) 厚生労働省HP.平成27年10月26日報道発表資料 乳幼児突然死症候群死亡者数の推移(人口動態統計).‹http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/0000101529.html›

43) Angle B, Burton BK: Risk of sudden death and acute life-threatening events in patients with glutaric acidemia type II. Mol Genet Metab 2008; 93: 36–39

44) Filonzi L, Magnani C, Nosetti L, et al: Serotonin transporter role in identifying similarities between SIDS and idiopathic ALTE. Pediatrics 2012; 130: e138–e144 [Epub 2012 Jun 18]

45) 山田恵子:乳幼児の小児一次救命処置に対する保育士の認識と現状.日本小児看護学会誌2012; 21: 56–62

46) 山下麻美,石舘美弥子,宍戸路佳,ほか:乳幼児視閲における小児一次救命処置に関する基礎的研究—市内の保育所幼稚園における自動体外式除細動器(AED)の設置状況—.小児保健研究2016; 75: 14–19

47) 日本心臓財団.AEDの具体的設置・配置基準に関する提言.日本循環器学会AED検討委員会.心臓2012; 44: 392–402

48) Mitamura H, Iwami T, Mitani Y, et al: Aiming for zero deaths: Prevention of sudden cardiac death in schools: Statement from the AED committee of the Japanese Circulation Society. Circ J 2015; 79: 1398–1401

49) American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP): 911 caller good Samaritan laws. Policy statement. Ann Emerg Med 2014; 64: 562 (doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.08.029). [Epub 2014 Oct 22]

50) Stewart PH, Agin WS, Douglas SP: What does the law say to Good Samaritans?: A review of Good Samaritan statutes in 50 states and on US airlines. Chest 2013; 143: 1774–1783

51) Bukowski JH, Richards JR: Commercial airline in-flight emergency: Medical student response and review of medicolegal issues. J Emerg Med 2016; 50: 74–78

52) 阿部百合子,鮎沢 衛,加藤雅崇,ほか:学校管理下における肥大型心筋症による心事故発生状況の変化.Pediat Cardiol Cardiac Surg 2015; 31: 240–245

53) 佐藤 誠,井上完起,石井 卓,ほか:ICD植込みの実際:AEDで蘇生された先天性心疾患症例6例の検討.Pediat Cardiol Cardiac Surg 2015; 31: 322–328

54) Suzuki T, Sumitomo N, Yoshimoto J, et al: Current trends in use of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy with a pacemaker or defibrillator in Japanese pediatric patients: Results from a nationwide questionnaire survey. Circ J 2014; 78: 1710–1716

55) Mitani Y, Ohta K, Yodoya N, et al: Public access defibrillation improved the outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in school-age children: A nationwide, population-based, Utstein registry study in Japan. Europace 2013; 15: 1259–1266

56) 循環器病の診断と治療に関するガイドライン(2014~2015年度合同研究班報告)『学校心臓検診のガイドライン』Guidelines for Heart Disease Screening in Schools合同研究班参加学会:日本循環器学会,日本小児循環器学会(班長:住友直方)